Other real options models that analyze a competitive industry equilibrium include Grenadier (1995, 2000) who models real estate markets with and without time-to-build, and Tvedt (2000) who analyzes the effects of the layup option on the stochastic process for shipping freight rates when different vessels have different operating costs. Leahy (1993) 84 points out the surprising result that the entry price in this case is identical to the optimal entry price of a monopolist who takes the price process as exogenous and ignores the effects of future entry on the price process. 83 Note that, once allowance is made for competitors, it is no longer possible to take either the present value of the investment opportunity or the output price as exogenous variables they must be derived as part of an equilibrium which considers the equilibrium optimal strategies of all firms. We will consider examples of the purely competitive and oligopolistic cases in turn. If the firm has a small number of competitors then the output price becomes endogenous, and must be solved for simultaneously with the optimal investment decision for all firms in this setting, the firm must weigh the benefits of waiting against the risk of pre-emption. The classic real options result that it is optimal to postpone an investment project relative to the Marshallian NPV Rule depends critically on the assumption that the firm is a monopolist with respect to the investment project, and that output prices are parametric. Brennan, in Handbook of the Economics of Finance, 2003 5.3.2 Multi-person games Using these inputs, real options analysis is performed to obtain the project’s strategic option values.” 17 In addition, the present value of future cash flows for the base case discounted cash flow model is used as the initial underlying asset value in real options modeling.

#REAL OPTIONS VALUATION EXAMPLES FREE#

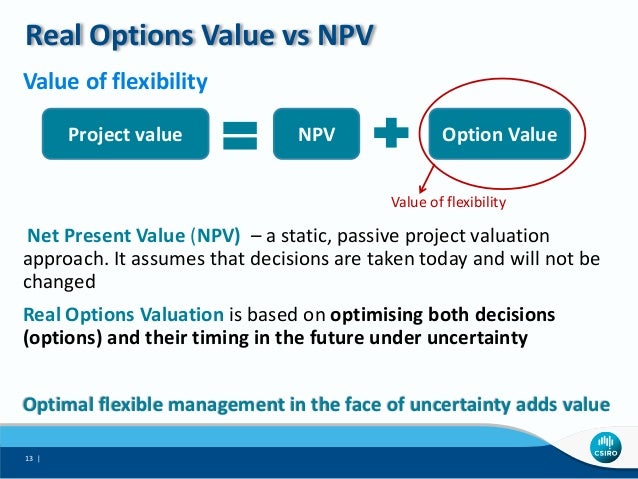

Usually, the volatility is measured as the standard deviation of the logarithmic returns on the free cash flow stream. An implied volatility of the future free cash flow or underlying variable can be calculated through the results of a Monte Carlo simulation previously performed. “In real options, we assume that the underlying variable is the future profitability of the project, which is the future cash flow series. Real options steer management toward maximizing opportunity while minimizing obligation, encouraging it to think of every situation as an initial investment against future possibility. Finally, deterministic NPV and IRR methods cannot value management’s ability to wait and learn, resolving uncertainty before investing. NPV cannot (or at best, can only inefficiently) value the management’s ability to abandon a project if it is unsuccessful. Net present value cannot evaluate management’s ability to invest now and make follow-up investments later if the original project is a success. A small change in the discount rate could have a considerable effect on the final output. As such, the discount rate used in the denominators of each present value (PV) computation is crucial in determining the final NPV number. NPV computations are simply a summation of multiple discounted cash flows, positive and negative, converted into present-value terms for the same point in time (usually when the cash flows begin). The biggest disadvantage to the calculation of NPV is its sensitivity to discount rates. With IRR models, computational anomalies can produce misleading results, particularly with regard to reinvestments. However, that measure does not tell us when a positive NPV is achieved. NPV models tell managers to accept investments where the NPV is greater than zero. NPV models disregard opportunities to alter investment game plans and consequently undervalue explicitly elastic projects. Simplistic real investment models popular before and during the debt crisis include net present value (NPV) and internal rate of return (IRR). Morton Glantz, Robert Kissell, in Multi-Asset Risk Modeling, 2014 Simplistic Investment Models

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)